There is a lot in common between human rights campaign and arts advocacy. Both address fundamental human values — self-expression, freedom, creativity, just to name a few. Yet the arts have multiple facets, media, and systems of signification. What makes interpretations of creative/artistic endeavor challenging (and fascinating) is that the arts often signify meanings far different from what was intended.

This essay is about a particular performance held in Vanderbilt Hall, Grant Central Station. I write as a spectator of a 20-minute performance in the context of the public setting.

Background

Chaw Ei Thien is a Burmese performance/installation artist who I got to know through a retreat hosted by freeDimensional in February. Her performance on June 22 was part of a day-long event organized by Human Rights Watch (HRW) in collaboration with JWT, an advertising agency. HRW aimed to gather signatures to send to Burma’s Senior General Than Shwe as a petition to free Burma’s estimated 2,100 political prisoners.

The Event

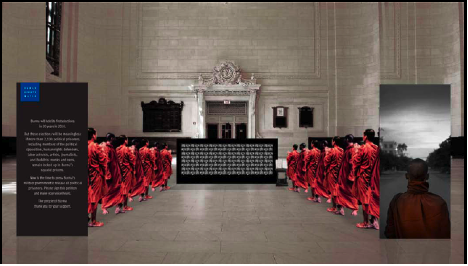

At 12:40 pm, about 40-60 people have already gathered in front of a large installation that looked like a giant wooden box (see picture at the end). I was soon greeted by a HRW staff encouraging me to take a pen from the exhibit and sign the petition.

It seems, however, most of the people around me either work for HRW, JWT, or they are Burmese activities and their friends. Every once a while, people who looked like tourists stopped and listened. So the number of the members of the public at any one time could be between 10-15. Granted, this does not detract from the integrity of the installation or the performances. It only makes me wonder about the efficacy of public exhibits/performances. It’s a point I shall return to later.

To set up the performance, Chaw placed a chair in the center of the ‘stage.’ On its right, she placed two (9′ x 11′) drawings, one of a motorcycle, the other an airplane. On the left, she placed a plate of rice, an empty can, and a plastic tub. In front of the chair, she placed a long piece of black cloth and another one with a middle section held together (by a flat plastic tube?).

Emerging from behind the installation, Chaw wore a long white tunic, her head was covered in a black cloth bag. She walked tip-toed with hands behind her neck. I could almost hear the audience holding their breath as she stumbled left and right towards the chair.

She knelt on the piece of black cloth and held her arms straight. At first it seemed as if she was being handcuffed. But she was moving her clenched fist. It looked as if she was riding on the motorcycle! She then stood up and extended her arms and stood on her right foot. She was flying (on the airplane). Vehicles that enable mobility — the motorcycle would let her get away fast, and the plane would take her out of the country. But a black hood covered her face. Could she see where she was going? Is she going anywhere at all or was it just a fantasy?

She then sat down and looped one side of the other strip of cloth through her right ankle, then another — it was a shackle. She began pacing around, still with hands held behind her neck. Her feet swung sideways as she stepped forward to the right, then to the left, bending forward, stood up, and then twisted.

It struck me that the hooded figure resembles the infamous photograph from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in which the prisoner stood on top of a crate. But the reference is a bit tenuous. Chaw’s hooded figure could be anyone who is incarcerated.

Soon, Chaw stumbled back behind the stage and returned with two bottles of water. With knees on the floor, she crawled with her heads held forward as if in chains. The slow pleading gesture seemed to hold us hostage as well.

After pouring the bottled water into the can and the plastic tub, she knelt again with hands behind her neck. Quickly, she started putting her hooded face into the plate of rice, knock over the can, then thrust her head into the water of the plastic tub.

The audience seems to have gasped. These violent movements aggravates our inability to stop/help her.

Then as silently as soon as she began, she took off her hood and grabbed the postcards she had previously placed under the chair and walked towards us. With water still dripping from her face and looking just a tad out of breath, one by one, she handed out her postcards and the performance was finished.

Chaw’s performance gave us a glimpse of the rawness of emotions. The black hood speaks of isolation, anonymity; the pouncing of her head into the water speaks of anguish, frustrations, and hopelessness.

Reflections of the Vanderbilt Hall event

In the hall, there was in fact no ‘on stage’ and ‘off stage’ distinction as onlookers were encouraged to squeeze behind the speakers to view the photos and sign the petition. Passive onlookers became active participants as they take a pen out of the light box to sign the petition, by doing so, they symbolically removed a prison bar.

As the sacred and the profane spaces are blurred, ‘off stage’ activities also becomes part of the petition campaign.

The passing tourists, office workers on lunch breaks, HRW staff zipping back and forth, JWT staff with their ironed dress shirts, Burmese monks and activists, and people in suits who looked like funders, etc, etc. A couple of (Burmese) women even posed for photos. One smiled sweetly in her pretty taupe color shirtdress with embroidered borders. Another wore a paper mask of Aung San Suu Kyi. A professional photographer adjusted her mask and bent her elbows to pose for the picture. The totality was surreal because there were so many different performances going on at the same time.

Moreover, since there were more event staff then people who were not, this petition event seems to be a well run event but it did not draw crowds. In an advanced media age when smart mobs and Youtube videos can go viral, the public-ness of this event remains a limited engagement.

The hiring of a big advertising agency for this HRW campaign also adds to the setting’s surreal quality.

When one of the speakers pointed to one of the photographs, I was surprised to hear that these are not anonymous individuals, but are actual political prisoners even though we can’t see many of their faces.

Why did the organizers omit their names from the installation? What are their stories? How long have each of them been in prison? If we were to symbolically free each one of them, shouldn’t we also know something about them as individuals? (Viewers should have been encouraged to go to 2100 in 2010 Free Burma website to find out more.)

I feel particularly critical about this point because I found out later that these pictures were Photoshoped to look hauntingly beautiful and stark. The clever montages transport the viewer simultaneously between Burma and New York. Yet the slickness of the packaging denies the ugly reality of prisons. It is too clean. The pens as prison bars is a nice idea, but is that supposed to empower us? just for a signature? Are there deeper ways to connect us to the issues?

Perhaps this is where we could distinguish between the installation and the performance.

Chaw’s hooded figure was anonymous as well. But one cannot mistaken her stumbles and jerky movements as aestheticisation. Her awkwardness embodies physical oppression and mental anguish. The resulting contrast could not be greater: while Chaw’s performance calls attention to the prisoner’s sufferings, JWT’s photographs draw attention to themselves as beautiful objects. The slick montages kept us at a distance. They remain exotic and foreign, like sepia photographs of the Ashes and Snow series. I only wish HRW’s well-funded campaign machinery could see this distinction.

Photomontage from JWT’s art installation brochure